Personalized Medicine in Cancer Therapy

Even though research, which is predominantly based on animal experiments, is still stagnating for many types of cancer, there are a variety of drugs available in addition to radiation and the surgical removal of the tumor. However, since the individual patients and their individual diseases differ significantly from each other – a circumstance that is not considered in animal research – it is necessary to select the most suitable medication for individual patients. Especially in cancer therapy, personalized medicine offers advantages because it takes into account that people are individuals, and their tumors are based on individual changes.

This article highlights how methods from modern animal-free cancer research can not only advance the development of new drugs, but also enable a therapy tailored to the respective patient.

Simplified models do not reflect the complex disease

Animal-experiment based cancer research uses so-called animal models, which differ in many ways from the affected patients. For tumor induction, the animals are often injected with cancer cell lines that have been grown in the laboratory for years or decades and are therefore significantly different from the tumors growing in patients. These cells are usually implanted in mice that have been bred to have a compromised immune system. The cells are mostly injected under the skin of the animals, regardless of the location of the original tumor, as this makes it easy to observe and measure tumor growth from the outside. Thus, the environment of the tumor in so-called animal models differs significantly from that in the patient: It contains cells, proteins, and messenger substances of the mouse, does not correspond to the environment of the organ in which the tumor was located originally, and has only a limited immune response (1).

In addition, the "animal models" are over-simplified and -standardized. For example, individual cell lines that do not reflect the complexity of the tumor, whose cells can differ greatly from each other (2), are injected into healthy, young, and mostly male mice belonging to genetically uniform inbred strains. This is done in the almost desperate attempt to obtain supposedly meaningful data by measuring the smallest possible effects on the particularly uniform animals. However, this approach in no way reflects the diversity of cancer patients and the complexity of their diseases.

Differences in patients and their tumors

Patients of both sexes and different age groups present themselves in oncology practices. They are genetically different from each other, have different pre- and concomitant diseases, their cancer is in various stages and has already been treated with different therapies. Even if the same organ is affected by cancer in two patients, the tumor cells differ significantly from patient to patient. Even within a tumor, the cells differ considerably (2). In addition, the tumor also changes over time and a therapy that initially works well by killing a portion of the cancer cells can become ineffective in the later course of the treatment.

The fact that tumors can differ and thus require different therapies is well known for breast cancer. Some types of breast cancer have hormone receptors on the surface of their cells that cause the tumor to respond to hormones. One such receptor is the estrogen receptor, to which the female hormone can bind, thereby stimulating the growth of the tumor. For such tumors, anti-hormone therapies can be used, which prevent the estrogen from docking to the receptor or prevent the production of estrogen (3). Women whose tumor carries the estrogen receptor can significantly improve their prognosis with anti-hormone therapies, while it would be useless for other patients. This makes it obvious that the selection of a suitable therapy should be based on the characteristics of the tumor cells of the respective patient.

Some of these tumor characteristics are already considered in the so-called S3 guidelines. These guidelines are compiled by experts based on their experience and contain recommendations for diagnosis and therapy. Thus, many tumors are already checked for the presence of individual surface proteins. In addition to the aforementioned estrogen receptor, the human epidermal receptor 2 (HER2) is also routinely tested in breast cancer. HER2 is a receptor that can stimulate cancer cells to grow and thus lead to a more aggressive tumor. To prevent this, antibodies that bind to HER2 and block the receptor can be used (4).

Methods considering the differences between tumors

Individual biomarkers or "sets" of several biomarkers are already routinely analyzed to enable the selection of the most effective therapy possible. However, in addition to the known receptors that have already been included in the S3 guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of various cancers, there are other characteristics of the tumor cells that can be important for the selection of a promising therapy. How can such factors, which can make the tumor particularly susceptible or resistant to a certain therapy, be considered when making a therapy decision?

There are a number of newer technologies originating from animal-free cancer research that allow for a more comprehensive analysis of the respective patient's tumor and with which patient-specific therapy recommendations can be evaluated.

Omics Technologies

The aforementioned hormone receptors on the cancer cells are proteins that are produced by the cancer cell and presented on the cell surface. They can be detected, for example, in tissue sections by using dye-labeled antibodies directed against the respective receptor. While this method is useful for the detection of individual surface proteins or a smaller number of such so-called biomarkers, it quickly reaches its limits if the properties of the tumor are to be studied more comprehensively and rare biomarkers or mutations need to be considered.

In that case, the so-called omics technologies offer a way to obtain a variety of information about the molecular properties of the tumor (5). This takes advantage of the fact that the genetic information for the production of the proteins, which influence the properties of the tumor, is available in the genome of the tumor cells. Sequencing of the DNA of the cells thus provides information about receptors existing on the cell surface, which can be crucial for therapy decisions. It also provides information about processes that can make cells resistant to certain drugs and can be used to identify genetic mutations that are responsible for the development and progression of cancer. This allows doctors to use targeted therapies such as immunotherapies.

Proteomics examines proteins in a cell or tissue. It allows the identification of specific proteins that are expressed by the cancer cells and could represent potential therapeutic targets (6). By analyzing protein interactions, the interplay between different pathways that contribute to cancer development can also be discovered.

So-called metabolomics can also be used to select suitable therapies. It analyzes the metabolites of a cell or tissue. Altered metabolic pathways are a characteristic feature of cancer cells. By studying the metabolome, evidence can be obtained about specific metabolic pathways that could be influenced by drugs (7).

The various omics technologies thus make it possible to obtain a comprehensive picture of the individual tumor and its biological characteristics. On this basis, the most appropriate therapies for each patient can be selected (8).

Liquid biopsies

Conventional omics technologies require tumor cells, which are usually obtained from biopsies or from a resected tumor. Since tumor components and DNA derived from tumor cells are also present in the patient's blood, it is possible to obtain the required material from a blood sample. This procedure is called liquid biopsy. Mutations in the DNA in the tumor can be detected by liquid biopsy and suitable drugs can be selected based on this information. Liquid biopsy also enables the investigation of tumor heterogeneity. Because different areas of a tumor may have different genetic mutations, it is possible that a tissue biopsy is not representative for the entire tumor. Here, a liquid biopsy can provide additional genetic information that takes into account the entire tumor and any metastases that may be present (9).

The method enables screening for early diagnosis, the detection of relapses, an estimation of the risk of metastasis as well as the identification of therapeutic targets and the resulting therapy recommendations (10). In addition, liquid biopsy is patient-friendly, as only a blood sample is required, and an invasive biopsy is not needed. It is currently under investigation whether even saliva and urine are suitable for testing for tumor-specific material (10).

Cellular systems

One limitation of omics technologies is that only known biomarkers can be identified (at the protein level or on the basis of their DNA) and only altered metabolic processes that are already known can be taken into account. In other words, it is only possible to find what is specifically searched for and what is already mechanistically understood. In this context, it could be useful to carry out an even more comprehensive examination of the tumor cells. Instead of detecting proteins on the cells’ surface or inferring on the presence of such proteins at the DNA level, the most direct access to information about a tumor’s response to different drugs is to directly study their efficacy on cells of the tumor (11).

For this purpose, biopsies are taken from the tumor or material from resected tumors is used. These tissues can be used to produce organoids, i.e., small 3D cell cultures, which can be used to screen potential drugs. In animal-free cancer research, this enables the identification of new drugs by bringing large libraries of substances into contact with the organoids and investigating whether they affect the growth or survival of the organoids (12).

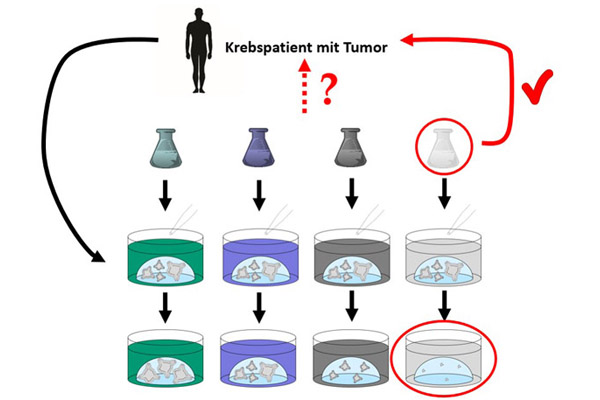

Organoids are grown from patient-derived tumor samples. These can be used to select the drug that most effectively fights the cancer cells of the respective patient (image source: Doctors Against Animal Experiments).

If the organoids are obtained from cells of a tumor of a particular patient, they are called patient-derived organoids (PDO). These organoids retain properties of the original tumor, the surface proteins on the cells correspond to those in the original tumor, and possible resistance of the tumor to certain drugs is also retained in the organoid (13). Organoids can be grown in the laboratory from samples of an individual patient's tumor and then treated with various possible drugs to identify the drug that most effectively kills or hinders the growth of the tumor organoids – and thus also the patient's tumor.

The use of tumor material thus provides immediate access to information about a possible therapeutic response without the need to know the underlying genetic alterations.

Aberrations of translational medicine

Even though patient-derived organoids provide ideal models for investigating individual tumors in the laboratory, some cancer researchers seem to be so caught up in their belief in so-called animal models that they also use them in the field of personalized medicine.

PDX model

For example, patient-derived tumor organoids are implanted into mice in the so-called patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model (14). Immunodeficient mice are used for this purpose. This means that the immune system, which plays a crucial role in the body's defense against the tumor, is not considered in the experimental setup. Also, the tumor is located in a murine (= mouse) environment and often the tumors in the mouse do not grow as desired. In addition, the "establishment" of such so-called xenograft models takes time, which many patients do not have. And even if the patient is still alive when the mice in which his or her tumor grows are ready to be used in animal experiments, the tumor may have changed significantly by then – both in the patient and in the mouse (14). Thus, the sobering conclusion remains that mice are abused as "cultivation vessels" for tumors, while the term "personalized medicine" promises a direct benefit for patients, which does not exist.

Mice are abused as "cultivation vessels" for tumors.

Testing on chicken embryos

Another negative spin-off of animal-based cancer research is the use of chicken embryos in personalized medicine (15). An opening is cut into the shell of fertilized chicken eggs. Then, cancer cells or pieces of the tumor are placed on the membrane of the chicken embryo. The eggs are then further incubated, causing the tumor to grow and tumor cells to spread into the chicken embryo as well. A considerable proportion of the embryos die during the experiments, the rest are killed a few days before hatching. The tumor is then "harvested" and examined (15,16). It is particularly disturbing that experiments on chicken embryos do not require a permit in Germany, since Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes only applies to and protects mammalian embryos, but not bird embryos (17). Thus, the cruel experiments on chicken embryos are even regarded as an "alternative" to animal experiments within the context of the 3Rs ("Replace, Reduce, Refine") (16).

Only completely human models are effective

The success in the development of new drugs is sobering, with an average failure rate of over 92% (18). In the case of anti cancer drugs, it is even worse: almost 95% of potential new treatment methods that have been tested as effective and safe in "animal models", fail in clinical trials on humans and do not reach the market (18).

Even the drugs that reach the patient often offer only a marginal improvement in terms of survival time and quality of life (19). One of the main reasons for this is the lack of translation from preclinic to clinic. Due to the differences between animals and humans, drugs that show high efficacy and good tolerability in animal experiments may have no effect or severe side effects in humans (20). More and more pharmaceutical companies are recognizing that animal-based research is not effective (21). Personalized medicine offers advantages, especially in cancer therapy, as it takes into account that people are individuals and that their tumors are based on individual alterations. The fact that the success of treatment already varies from one patient to another also shows that animal-based research simply cannot work.

Opportunities for oncologists and their patients

Personalized methods are increasingly being used in cancer research and are also becoming more available to physicians and their patients. In this way, they enable a personalized therapy decision optimally tailored to the respective patient and his or her individual disease. Omics technologies or organoid-based screening approaches can be used to identify the most effective therapy without first carrying out therapies that may be ineffective and associated with side effects under a "trial and error" approach, which does not benefit the patient but cost valuable time.

In order to give patients and their physicians access to these technologies, some companies offer them as a service. For this purpose, samples, i.e., tumor tissue or blood samples, are sent to the companies where the examinations are then carried out. Tailored therapy recommendations are derived from the results and made available to the oncologist in a report. In some cases, in addition to standard drugs, currently open clinical trials are also considered and are recommended to suitable patients, who could benefit from them. Some of the companies that offer these methods are listed below (see box).

A guide to tailored therapy

In the following, options of easy access to a comprehensive tumor diagnostics and the resulting personalized therapy recommendations for oncologists and their patients are shown. The list does not claim to be complete. It is only intended to provide information about the range of possibilities and to enable an easy contact with a focus on Germany.

Omics technologies

Omics-based personalized therapy decisions are offered, among others, by the Centers for Personalized Medicine (German: Zentren für Personalisierte Medizin, ZPM). Omics analyses are carried out in particular when the guideline therapy has been exhausted or does not promise success, as well as in the case of very rare tumor diseases. In particular, genetic analyses of fixed tumor tissue using Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) and immunohistochemical staining methods are used for functional analyses. Analyses of tumor metabolism are also possible. The therapy recommendations prepared by interdisciplinary molecular tumor boards also consider drugs outside their actual approval (off-label), as well as individualized therapeutic approaches such as cell-based therapies and immunotherapies, if the molecular profile is suitable. ZPMs can be found in Heidelberg, Tübingen, Freiburg, and Ulm, among others. Further centers can be found on the website of the German Network for Personalized Medicine (German: Deutsches Netzwerk Personalisierte Medizin, DNPM) (22). According to the DNPM, the statutory health insurance covers the costs if a guideline-compliant therapy is not (or no longer) available or promising.

Foundation Medicine (Roche) also offers various molecular tumor profilings for different tumor diseases (23). The resulting report provides insights into the molecular tumor profile as well as related potential targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and respective clinical trials. In addition, genes associated with possible drug resistance are identified, sparing patients potentially ineffective treatments. According to Foundation Medicine, a reimbursement by health insurance is possible based on an individual case decision.

Liquid biopsy

Foundation Medicine also enables the analysis of blood samples for genomic alterations in over 300 cancer-related genes. This enables patient-friendly diagnostics without biopsy as well as follow-up, control for recurrences, and patient-specific therapy recommendations (23).

Patient-derived tumor organoids

The company ASC Oncology offers the screening of various drugs using patient-derived tumor organoids. During tumor surgery or biopsy, a small piece of freshly removed tumor tissue is placed in a sample tube and sent to the laboratory by express courier. The patient-specific tumor models produced from the sample are used to test the effectiveness of various drugs. As a result, possible unknown genetic changes are also taken into account without the need for any knowledge about them. The testing includes cytostatics, targeted therapies, antibodies, drugs in off-label use, current clinical investigational drugs as well as experimental, alternative medicine or naturopathic drugs as single or combination therapy (24). Organoid-based diagnostics is an individual health services (IGeL), an application for reimbursement by the health insurance companies is possible, for which ASC Oncology provides forms.

Personalized medicine for other diseases

Other diseases than cancer also differ greatly from patient to patient and there are personalized approaches originating from animal-free research in other areas, too.

Patients with cystic fibrosis can benefit from these new developments, for example. In cystic fibrosis, there is an alteration in the CFTR (Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator). This is a protein that forms a channel on cell surfaces through which salt can leave the cell. Various mutations of the CFTR gene cause the salt to accumulate in the cells in cystic fibrosis, causing the environment of the cells to dry out and, for example, the mucus in the lungs to solidify. The CFTR gene can be altered in a variety of ways (about 2,000 mutations are known to date), which makes it difficult to select a therapy that is suitable for each patient (25).

To be able to select a suitable therapy, a screening procedure with patient-derived intestinal organoids was developed. The organoids are treated with various possible drugs. Then a chemical is added, which causes swelling of the cells in organoids with functional CFTR, but not in organoids with defective CFTR. In this way, drugs that restore the function of the CFTR in the organoid model can be identified and then used to treat the patient (26). At the Microphysiological Systems (MPS) World Summit 2023, it was reported how the procedure was successfully used to select an appropriate therapy that dramatically improved the health of a patient with a rare mutation that is not included in the S3 guidelines and for which no therapy recommendations are available (27).

Conclusions

Personalized medicine is a prime example for the efficiency of animal-free methods. While animal experiments fail due to the differences between animals and humans, personalized medicine not only delivers human-relevant results, but also data for individual humans. The potential of personalized medicine extends from cancer research to clinical trials. In cancer research, patient-derived organoids allow for research on a human model and for the consideration of patient-specific differences in drug development.

Personalized medicine opens completely new opportunities for oncologists and their patients beyond research: Patient organoids or DNA analyses enable evidence-based therapy selection that is optimally tailored to the respective patient and his or her individual cancer. As a result, the patient can receive the most effective therapy and unnecessary therapies - which are not effective but associated with side effects – can be spared. Thus, personalized therapy decisions will lead to significant improvements for the patients and to substantial savings in the healthcare system.

14th August 2024

Dr. Johanna Walter

References

- Cancer: Animal experiments and animal-free research, 2023, https://www.aerzte-gegen-tierversuche.de/en/specific-infos/science-medicine/diseases/cancer-animal-experiments-and-animal-free-research

- Sun X. et al. Intra-tumor heterogeneity of cancer cells and its implications for cancer treatment. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2015; 36(10):1219–1227

- German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ): Breast cancer: anti-hormone therapy (in German), https://www.krebsinformationsdienst.de/tumorarten/brustkrebs/hormontherapie.php#collapse1

- Ishii K. et al. Pertuzumab in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer: an evidence-based review of its safety, efficacy, and place in therapy. Core Evidence 2019; Volume 14:51–70

- Rossing M. et al. Whole genome sequencing of breast cancer. APMIS 2019; 127(5):303–315

- Su M. et al. Proteomics, Personalized Medicine and Cancer. Cancers 2021; 13(11):2512

- Jacob M. et al. Metabolomics toward personalized medicine. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 2019; 38(3):221–238

- Chen R. et al. Promise of personalized omics to precision medicine. WIREs Systems Biology and Medicine 2013; 5(1):73–82

- Hemenway G. et al. Clinical Utility of Liquid Biopsy to Identify Genomic Heterogeneity and Secondary Cancer Diagnoses: A Case Report. Case Reports in Oncology 2022; 15(1):78–85

- Lone S.N. et al. Liquid biopsy: a step closer to transform diagnosis, prognosis and future of cancer treatments. Molecular Cancer 2022; 21(1):79

- Yang H. et al. Patient-derived organoids: a promising model for personalized cancer treatment. Gastroenterology Report 2018; 6(4):243–245

- Kondo J. et al. Application of Cancer Organoid Model for Drug Screening and Personalized Therapy. Cells 2019; 8(5):470

- Abugomaa A. et al. Patient-derived organoid analysis of drug resistance in precision medicine: is there a value? Expert Review of Precision Medicine and Drug Development 2020; 5(1):1–5

- Harris A.L. et al. Patient-derived tumor xenograft models for melanoma drug discovery. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2016; 11(9):895–906

- Chu P.-Y. et al. Applications of the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane as an Alternative Model for Cancer Studies. Cells Tissues Organs 2022; 211(2):222–237

- Ranjan R.A. et al. The Chorioallantoic Membrane Xenograft Assay as a Reliable Model for Investigating the Biology of Breast Cancer. Cancers 2023; 15(6):1704

- Directive 2010/63/EU oft he European parliament and the council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes

- Biotechnology Innovation Organization, Informa Pharma Intelligence & QLS Advisors, New Clinical Development Success Rates 2011-2020 Report, https://www.bio.org/clinical-development-success-rates-and-contributing-factors-2011-2020

- Davis C. et al. Availability of evidence of benefits on overall survival and quality of life of cancer drugs approved by European Medicines Agency: retrospective cohort study of drug approvals 2009-13. BMJ 2017; doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4530:j4530

- Loewa A. et al. Human disease models in drug development. Nature Reviews Bioengineering 2023; doi: 10.1038/s44222-023-00063-3

- Frankfurter Rundschau, 26.05.2023, Merck CEO speaks out in favour of phasing out animal testing (in German)

- https://dnpm.de/de/zentren-des-dnpm/

- https://www.foundationmedicine.de/de/our-services/our-portfolio.html

- https://www.asc-oncology.com/

- Mukoviszidose e.V.: The causes of cystic fibrosis (in German), https://www.muko.info/mukoviszidose/ueber-die-erkrankung/ursache

- HUB ORGANOIDS: Forskolin-induced swelling assay, https://www.huborganoids.nl/forskolin-induced-swelling-fis-assay/

- MPS WS Abstract Book. ALTEX Proceedings 2023; doi: 10.58847/ap.2301